... well, certainly not virtue!

In terms of the Heroic Journey, I see my years with the Stepmother as a significant ordeal, after which I received some rewards such as coming under the care of my nice aunties, attending university, making new friends, and finding my first love (even though there was sorrow involved in that). But the ordeal had not really been dealt with or resolved. The further ordeal of a stressful first marriage, with some bizarre and even crazy aspects, was what I needed to claim the reward of real resolution. You might not think of entering psychiatric treatment as a reward, but for me it absolutely was – a great gift for which I remain fervently grateful.

Therapy

I embarked on what would become six years of group psychotherapy. The Doc, as we all called him affectionately behind his back, explained that he preferred to use group therapy because it enabled him to charge each individual patient a lot less and still earn what he needed to, and because, 'If one person is telling you you're being paranoid, you might doubt it; but if a whole group of people is telling you so, it's harder to dismiss'.

I was very lucky in being referred to that particular psychiatrist, as I realised later when I heard stories about how unsatisfactory some others were. He thought of his patients as people, not as illnesses or labels: as 'Mrs Freeman' rather than 'that woman with anxiety'.

'Anxiety state' was my official diagnosis. I always thought that was simply a convenient label because I had to be diagnosed with something in order to claim medical benefits. I suppose that hallucinating skulls over people's faces and having to be sedated after a party could be viewed as extreme anxiety!

In the course of our first, one-on-one conversation, at one point he approvingly responded, 'Good girl!' to something I said. Instantly triggered, and to my own surprise, I yelled, 'I don't want to be a good girl!'

'What do you want to be?' he asked, but for that I had no clear answer. I didn't want to be a bad girl either – not outright nasty, not evil. Probably, what I really didn't want was to be conformist, to perform a role.

It appeared there was some division between aspects of myself. He promised that by the end of my treatment they would be beautifully integrated.

One thing I thought I was there for was to cure what I perceived as my frigidity – forgetting how passionate I had been with John. All the foreplay was fine with Don, too, but when it came to penetration, I had very extreme reactions. I went into uncontrollable shrieks of terror without any rational basis, and my vaginal muscles clamped tight shut (a condition known as vaginismus). Don did suggest that he might be part of the problem.

'If I was a different kind of man ...' he said. Spelling it out: 'You could be raped.' I wasn't so sure.

In the course of my therapy, I uncovered a memory of a woman telling me, when I was a child, that men had great big things like red-hot pokers to stick into women. I thought it was my mother who told me that. Years later when I confronted her with it, she was horrified. And indeed, common-sense tells me now that she would never have said or even thought such a thing. She was furious that anyone would have told me that. She thought it must have been the woman who came in every week to help with the housework while she was expecting my brother. I'll never know.

Early on, we had psilocybin as part of our therapy. That was the term the Doc used, adding that it was the synthetic version – in other words, LSD. He told me it would act like a corkscrew to lift the lid off my subconscious, and that the advantage over hypnotherapy was that I would be able to split my consciousness into the experiencer and the observer. (With hypnotherapy, he had to tell the patient afterwards what transpired during the session.)

Patients would book in as outpatients for one day at a private hospital, lie down in separate rooms and be given what I believe was a small dose of the drug. It did exactly what I had been told it would: I re-experienced childhood events, with my adult consciousness alongside to observe and interpret them. This included some events I had always consciously recalled, others which I had forgotten but remembered when they were brought to the surface again, and some which I needed help to understand – such as seeing, as an infant, a large area of black-and-white squares, which the Doc suggested might have been the chequered pattern of someone's clothing.

I imagine that the more bizarre experiences under the influence, which recreational drug users have reported, would involve much larger doses – and also the lack of that simple explanation about the corkscrew, to put them in context.

We were monitored during the treatments, and given another tablet at the end (I don't know what) to bring us back to normal. Then we would meet as a group and discuss what had happened. I found it illuminating. But after some months these treatments were discontinued. Evidence came to light that there could be genetic side-effects, so the psychiatrists using this drug stopped at once rather than put their patients at risk. After that we reverted to weekly group therapy, 'the talking cure', in the Doc's professional offices.

One day, lying on the hospital bed – I don't recall what triggered it – I had an experience as if I was melting. It wasn't scary, it was blissful. But it involved a physical flowing from various orifices: tears, snot, saliva, as well as blood and some tissue from between my legs. I went to the toilet and cleaned myself up. It wasn't my imagination and it wasn't my period either. It was the spontaneous coming away of my hymen! The Doc was a rational, scientific man (albeit Jungian). As he once said, he didn't deal in miracles; if that's what we were after, we were in the wrong shop. So he was taken aback when I reported that experience, but he accepted that it had happened.

It didn't lead to a consummation of the marriage. I look back now and find I don't recollect any details about why that was. Perhaps it was because Don wasn't well. He ended up in hospital, briefly, with a kidney stone. Perhaps it was because I had already given up on the marriage. It had got to the point where we hardly communicated. He began spending a lot of time going out with his mates and coming home drunk. For a while I kept on desperately trying to make our marriage work, until it dawned on me that I was the only one still trying. That couldn't work!

Satisfaction

Meanwhile, I wanted to experience sex. I propositioned a married man I knew. It was common knowledge that his marriage was no longer a sexual union; his wife didn't like it. One might wonder whose fault that was – but I soon found out that there was nothing wrong with his performance. Far from it! Nor did I have the extreme fear responses by then. (Yes, therapy does work!) I also realised, once I had someone to compare him with, that Don was semi-impotent.

I confessed my infidelity, and we agreed to separate. He decided to move to Sydney and start over. He actually helped me move to a new flat and let me keep most of our stuff – of course including our tabby cat, Guinivere, no longer a kitten, who was with me the rest of her life to the age of 18.

My Guinivere, 1965

Before he left Melbourne he visited me often, we went out together, and it was like our courting days all over again. Don and I got on beautifully and had a great time with each other so long as we weren't actually living together.

I decided to take him to bed, now that I knew how to go about it. I felt I owed it to him. And yes, we did finally manage it. He said – heartfelt – that it was wonderful. Then he confessed that he had never before succeeded in making love to any woman. (People have since speculated that he may have been gay, perhaps suppressing it. I don't know, but I think it's unlikely. He was very interested in heterosexual porn – not movies, in which one might suppose he could have been looking at the men, but books – books written for straight men.) We knew this belated success wasn't a reason to resume our marriage, though. Our incompatibilities were many, and that had become obvious to us. We really had almost nothing in common.

When, along with several of his friends, I saw him off on the train to Sydney, he and I both cried. His friends told us we were being stupid and obviously shouldn't be parting if it upset us so much. But we knew it was right. We had entered into the marriage in good faith, we began and ended it as friends, and in some ways we'd shared a lot. We did care for each other, but it wasn't enough.

I knocked up some friends close by and had a tearful coffee with them, then went to catch my bus. It was late by then. As I stood alone on the deserted street corner, one of the 'gutter crawlers', who were notorious in those days, slowed and rolled down his window. I was emotionally at the end of my tether. Instead of being fearful, I stepped up to the car, bent down and thrust my face, contorted with fury, close to his. 'You get out of here and you leave me alone!' He was the one who looked terrified as he sped off.

The affair was wonderful, and we did have heaps in common even out of bed. The essential secrecy was a drag, though. And it becomes disappointing to have wonderful love-making with someone who then, instead of staying all night in your arms, has to get out of bed and go home to his wife – repeatedly. It was the old story: he had young children he loved. He didn't want to lose them, nor in any way disrupt their lives. He agreed to the affair in the first place on the condition that it must remain absolutely secret.

We did fall in love, in a grande passion. As he said at the time, 'Love can have everything to do with sex or nothing to do with sex.' In our case it was everything. He was a very sexual man. It was even more important to him than it is to most people. I was by no means his first affair, but I think the one that meant the most. Sadly for him, that did not remain so for me. I went on to break his heart when I ended it. He was devastated, and it was made worse by having to try to appear normal because it was all a secret. When we had occasion to meet at a function a few years later, and needed to greet each other in public and exchange some conversation, he could barely get the words out. Then, when I mentioned my young children, he suddenly looked purposeful, said something about the vital role of parents, gazed meaningfully in my eyes and said, with emphasis, 'Never forget that YOU are a very important person.' I reeled a bit and acquiesced, and that was the last time I ever saw him.

Decades later I read a death notice. He had had a very successful, even distinguished career, and a long second marriage to a woman whom he had been having an affair with when I came on the scene. He had ditched her for me, which I didn't know at the time – never occurred to me he might already be straying from the sexless marriage. He did tell me about it later, and it was clear it had been a very compatible relationship. He must have gone back to her. Evidently she forgave him; I guess she truly loved him. Once his children were grown, he'd have had no reason to stay with his first wife. I'm glad to think there was life after Rosemary, a happy and fulfilled life.

When we were together, we had vowed to each other to meet in eternity and be together forever. I'm a psychic medium; spirits sometimes contact me. His spirit sought me out soon after he died, to reiterate that vow. But I hadn't loved him deeply after all. I told him no, I was withdrawing that promise and releasing him from his. There was someone else I wanted to spend eternity with. (Imagining eternity in terms of monogamy, I note now!)

While we were having our secret affair, there was no ostensible reason I couldn't have other men friends. In fact it could be a way of throwing people off the scent. I didn't plan to sleep with them, of course. I got a phone call from a man I had met at a friend's wedding, Dutch-born Bill Nissen.

New Horizons

I'd attended that wedding with Don; it was near the end of our marriage. Bill was newly-engaged, but his fiancée had been unable to come to the wedding. Don was flirting with everything in sight and I was trying to maintain my dignity by ignoring it. Bill and I got talking, just in a casual way, for lack of anyone else to talk with.

Don and I had come to the wedding in a taxi. When it came time to leave, Bill offered lifts to a few people who were going in his direction. We all piled into his car, a tight squeeze, with me sitting on someone's knee. (You could do that then, before seat belts.)

I learned afterwards that Bill had been shocked to find himself wishing it was his knee I was sitting on – shocked because I was a married woman. But he put it out of his mind. Over the next few months he broke off his engagement and booked to go on an overseas cruise, with the idea that he might stay away indefinitely. Then, he met for coffee with an old friend who had been bridesmaid at the wedding where we met. She mentioned that Rosemary and Don had split. When he told me about it later, he said he could feel his eyes light up.

'Hey,' said his friend, 'Don't go getting involved. You've just booked on this big trip you've been dreaming of all your life.' But he phoned me anyway.

'I believe you have a degree in English,' he said. 'I'm writing a novel and I'd love some help with my English.'

'Oh yes, ha ha,' I thought, 'A novel pick-up line, anyway.' I didn't say that, of course.

I actually had him mixed up in my mind with another guy who'd been at the wedding. When he turned up at my work to fetch me when I knocked off, I didn't recognise him until he came up and spoke to me. (I don't think I ever told him that.) He took me on a nice, safe date to visit the friends at whose wedding we had met. At one point in the evening, he knelt at my feet, gazed rapturously up into my face, and whispered, 'Are you enjoying yourself, darling?' I was startled at the 'darling' but he seemed to be genuinely concerned that I was having a nice time.

We started spending time together, platonically. He was about to go overseas, we'd both come out of relationships quite recently ... and I did tell him I was involved with someone else, but not who. We enjoyed each other's company. We were just going to be good friends.

Bill was a person who loved to help others. When my TV broke down, he came and took it away in his ute to a mate who fixed it as a favour. He would pick me up from work and take me shopping so I didn't have to lug groceries on public transport. He'd come around on weekends when my lover was with his family, and keep me company.

We would have long talks, sitting in separate armchairs, never running out of topics. He was in fact writing a novel, and told me the plot, though I didn't get to see the manuscript until much later. One night, after he finally left, I saw that it was 3am. I hadn't even looked at the clock before then. He told me later he'd had the same surprise on the way home when he drove past a big public clock. We laughed to think no-one would ever believe we had been sitting in separate chairs talking all that time. All our friends would be certain we were having a red-hot affair.

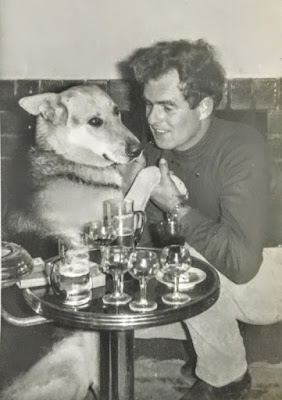

He was living with his parents. He told me about his beautiful dog, a German Shepherd called Gigi, who was the love of his life, went almost everywhere with him, and was jealous of his girlfriends. He had a story about one young woman who wasn't a girlfriend but came up close trying to be flirtatious. Gigi stood on her hind legs, put a front paw on each of the girl's shoulders, and snarled softly into her face. It thoroughly discouraged her!

Bill and Gigi

I was rather apprehensive about meeting this Gigi, and wondered if she would attack me. Bill said, reprovingly, 'Gigi is a lady' and assured me she would come to love me. When he finally brought her around to visit, she went one better than that. She came up to me, sniffed me, and nuzzled my hand for a pat. Bill was amazed and ecstatic.

My cat, Guinivere, lived outside all day while I was at work. When I got home, she would meet me at the gate then rush ahead of me down the path to my front door. As soon as I opened the door, she'd dart inside to the kitchen for me to feed her. One evening, Bill brought me home, Guinivere met us at the gate, I rushed to open the door for her, leaving him to get the groceries out of the car – and Guinie turned around, retraced her steps, waited for him to come in the gate, then walked beside him down the path. Again he was ecstatic. We said later that the animals made up our minds for us. But in truth we waited until our own minds caught up – which didn't take long.

One day I looked at him and thought, very quietly, 'Oh. I love you.' No bells, no fireworks, just the recognition of a fact. Almost at the same moment, he turned to me and said, 'I love you,' with an air of mild surprise. This was a love that had nothing to do with sex, based on shared interests, friendship, respect, affection, and feeling very comfortable with each other. Naturally it became sexual after that and I broke it off with my lover.

I insisted Bill should have his overseas trip. He had indeed been dreaming of it for years. Before he went, he introduced me to his family and all his friends. His parents were disappointed. They had a nice Dutch girl lined up for him, a pretty lass who could cook and sew and wanted babies. Bill had taken her out a couple of times to please them, but said they found nothing to talk about. His parents were nice to me, but I know I was not their notion of the ideal daughter-in-law – a divorced woman, a career-woman.

By then I was Deputy Librarian at the municipal library where I worked – at that time, and perhaps since, the youngest Deputy Librarian in the Southern Hemisphere. (When the position became vacant, all the other staff, who were my friends by then, urged me to apply. So did my boss. I wouldn't have thought of it for myself.)

This time I was prepared to contemplate the idea of having children, particularly as Bill loved kids, but I wasn't in any hurry and neither was he. We thought we'd get a home established first, and some money behind us. Anyway, he had this overseas trip to do before any of that.

Most of his friends welcomed me. One, a woman who was best friends with his ex-fiancée, spent the whole evening when we visited her discoursing on why he should still be with his ex! Another woman also tried repeatedly to persuade us we were making a great mistake. She had been out a few times with Bill and then married someone else after he ended it because, as he told me, he just wasn't all that attracted to her. (Her story, which I had heard earlier, was that she had ended it because she decided she could do better!) However, these were the exceptions.

My friends liked him too, and thought him a great improvement on Don. Mum at first wrote to me: 'We feel it's far too soon after your recent break-up for you to be contemplating another marriage,' but when I phoned her and told her it was my decision thanks very much, she offered to come over and meet him. He charmed her! She went home much happier.

He asked his family and friends to please keep an eye on me while he was away. The only one who did was his best mate, Jim Cathcart. Jim was a rep (I can't remember what for ... maybe menswear) who used to travel around the suburbs visiting his firm's clients. Whenever he was near where I worked, he'd come and take me out to lunch and see how I was going. He became my friend in his own right. When his territory extended to Launceston, Tasmania, I told him to look up my Mum and stepfather. They made him very welcome and they all got on famously. He always used to see them after that, when he went to Launceston.

But I wasn't doing very well. I couldn't go out and socialise as a single woman any more without attracting unwelcome advances, and I couldn't go out as half a couple when the other half was so far away. When I wasn't at work, I felt desperately lonely. And for ages no letters came from Bill. It was evidently a posting problem as suddenly several arrived at once. I tore open the first and nearly cried. I couldn't understand it! It took me some days to realise that he was spelling everything as it would have been spelt in Dutch to make those sounds. Then I was gradually able to work it out. Meanwhile I was writing him letters furious with frustration, complaining about how I was scrubbing my floors until midnight to try and work off my sexual energy.

I had vivid dreams about him. One time I even had what was apparently a hallucination. I had lain down on top of the bedclothes for an afternoon nap, and half woke to find someone lying next to me and hugging me. I felt the bed sink to accommodate their weight, I felt their arms come around me. I thought it must be a dream, but I wasn't quite sure. Without opening my eyes, I asked aloud, 'Who is it?' A hoarse male voice whispered in my ear, 'It's me.' I opened my eyes and there was no-one. The bed was smooth. My mind went spinning and somersaulting as if in a vortex; I thought I was going mad. But I gradually calmed down, the room stopped spinning, and (apart from what had happened) I didn't seem to be crazy. It must have been an exceptionally vivid dream, I decided.

So when I answered a knock on my door one morning and opened it to see Bill standing there beaming at me, for a moment I thought it was another dream. Then I noticed he had a suntan which hadn't been there last time I saw him. He must be real.

'Yes darling,' he said. 'Your husband's home.' (He wasn't officially my husband yet, but had every intention of being.) He'd received one of my furious letters and immediately cut his trip short.

He'd sent a telegram to his parents asking them to book him on a flight home. It turned out the poor things thought he must have been taken ill, or perhaps robbed. He expected that I'd be with them when they met him at the airport. The first thing he said to them was, 'Where's Rosemary?' Then he learned that they had not told me, nor contacted me at all during his absence. (I think they hoped our attachment would fizzle out while he was away.) He insisted on being dropped off at my place, which he said surprised them. But after that I guess they knew he meant it, and accepted the fact that he was going to marry me.

I myself wasn't too damn sure about getting married again. I'd done it once and that hadn't worked out. 'If I'm planning to spend the rest of my life with you anyway, what does the bit of paper matter?' I asked him. He hadn't done it before, however, and he was very keen to shout our love from the rooftops and make it as official as could be. So we were at an impasse. I thought he was beginning to come around to my way of thinking; then one day when we were visiting his parents, his mother, who had completely accepted and befriended me by then, mentioned the new hat she was making for our wedding. I didn't have the heart to tell her there wasn't going to be one. Oh well, I thought, if the bit of paper doesn't matter one way, I suppose it doesn't matter the other way either.

First I had to get divorced. Don and I were in touch by letter. He had a new job and a new girlfriend in Sydney. It was before the days of no-fault divorce; one of us had to be 'guilty'. Desertion would take three years; adultery was quicker. He wasn't willing to shoulder the blame, even though he was in a new relationship. We left my married ex-lover out of it; Don came to Melbourne for the divorce hearing and told the magistrate that we had been having a trial separation when I had written and told him I had met Mr Nissen, had started living with him and wanted to marry him.

The magistrate asked Bill, 'Did you know she was married?'

'Oh yes,' said Bill cheerfully, 'I knew'.

The magistrate then asked whether Don was claiming damages or property. Don said no. The magistrate expressed surprise that he was so generous, and granted the divorce. The three of us went and had a cup of coffee together, exchanged some meaningless but amiable remarks, then Don walked out of my life – very straight-backed, knowing our eyes were on him; not turning his head – to catch his train back to Sydney.

Bill had a coffee lounge before I knew him, the first in Melbourne to feature jazz musicians playing to the patrons. It was in Frankston and was called The Cat's Whiskers. As a keen snorkeller, he had also run a diving school. But when I met him he was working for his father as a builder, along with his elder brother. So when he bought us a house in the leafy bayside suburb of Beaumaris, it was one that needed some work, which he could renovate himself, saving money on both the sale and the work.

One of my other lifelong best friends, Pam, came into our life. She came to board with us, in the spare bedroom. There was also a bungalow in the back yard, which we rented out to a young couple; the man was an old friend of Bill's. And I still had my lovely cat, Guinivere. We didn't have Gigi. Bill's parents had looked after her on his brief absence overseas, and when he came home and moved in with me, they begged him to leave her with them. He still saw her every day, as his dad brought her to work.

We acquired another dog, a beautiful Scotch collie called, unoriginally, Lassie. She belonged to a young man we knew who was changing his address and was not able to take the dog with him. She was a very wise and wonderful dog, who became a treasured member of our family for many years, until she died of old age.

I wanted to avoid running into my ex-lover, which was likely if I'd kept the same job, so I got an even better job, as Head Cataloguer at a big technical library in the city. I had to learn a different classification system, but I enjoyed the learning. They thought I was wonderful because I cleared their cataloguing backlog in record time. It was nothing to the backlog I'd been used to in a municipal library.

This was a time when it was socially unacceptable to 'live in sin' as it was still called. Bill and I were living together, so I used his surname even though we hadn't yet made it legal. That's what 'de facto' couples did then. We started out renting, not in the little flat I had when we met, but one he found us closer to the library where I was first working, and also with less travelling time to his work. No-one would have rented to us had we not presented as a married couple.

In the paperwork required for the new job, my real status must come out. I confided in my new boss, a lovely older woman. She advised me to make an appointment with the Personnel Manager and disclose it to him in confidence. The fact that Bill and I had set a wedding date probably helped; anyway the disclosure was treated with great respect and complete confidentiality. Having begun a new job, I wasn't eligible for leave so soon. We didn't have a honeymoon, just a long weekend at home. We made up for it with lots of travels later.

My Second Wedding

We got married in the Unitarian Church, because at that time of our lives we liked their ideas. I was 25 and Bill was 28. I wore a pale pink dress. 'Slightly scarlet,' I joked. This time my stepfather did attend. I didn't bother asking my father. After I married Don, I graduated as a Bachelor of Arts. I invited Dad to my graduation ceremony, telling him that Mum would be there but hoping he would come anyway. He didn't. He expressed disappointment that Mum didn't have the tact to stay away. He said he thought a girl needed her mother on her wedding day, but it would have meant so much to him to see me graduate. Well, it meant a lot to my mother too, and my position was that I gave both of them the choice to come, to my first wedding and to my graduation, and whoever declined was refusing to put me first on one of my special occasions. Under the circumstances, it would obviously be a waste of time to ask him yet again. I didn't see why I should punish my mother, who was prepared to come under any circumstances.

The wedding reception was in our home, where we'd been living for some months. The renovations were nearly completed, but not quite. My mum, who set great store by appearances, went around draping tea-towels over exposed beams. I came home, threw a tantrum at the sight, considering it disgustingly twee, and ripped them all off again.

It was one of those days when everything goes wrong. For example, the flowers didn't arrive; the florist had messed up the order and had to hastily supply something that wasn't what I'd had in mind, after heated phone calls back and forth. We were so stressed that at one point, as we stood either side of the double bed we'd been sharing for months, I yelled at Bill, 'I wouldn't marry you if you were the last man in the world!'

'Well, how do you think I feel?' he bellowed back. Then the ridiculousness of it struck us, we collapsed on the bed in laughter, got up and finished dressing and went off to the church to get married.

Just married

I'd decided to leave my glasses off, and I wore a fluffy white hat that came down over my ears. Bad choices! I went up the aisle feeling blind and deaf as well as nervous. But we tied the knot, everyone said it was a lovely ceremony, and the party afterwards was fantastic. We catered it ourselves, with lots of food from the local Chinese takeaway. I remember my stepfather cheerfully washing dishes, having a ball. My friend Diane remembers Bill's mother regaling her with tales of his childhood. Jim Cathcart, who was Bill's best man, met a lovely young woman called Joy, one of our other guests, who eventually became his wife.

Jack washing dishes

One young woman, Elizabeth, had arranged to stay the night. We put a spare mattress on the floor in Pam's room. Elizabeth succumbed to alcohol and went to bed a bit early. Bill went to check on her, bending down to where she lay. Tipsy Elizabeth murmured, 'You married men are all the same' – much to his amusement – before collapsing.

Bill's muso friends and others from his coffee lounge days were playing guitars and other instruments in our big garage, where we'd put chairs, trestle tables, drinks and food. They used to call themselves, collectively, 'the tribe'. I was very chuffed when one of them said to me, that night, 'You were always one of the tribe, Rosemary.'

Lassie was at the wedding reception too

(this photo taken outdoors)

It was the wee small hours by the time everyone called it a night. I changed into my wedding night outfit: not a romantic, flowing nightgown but a pair of sexy red bikini pyjamas. But I was exhausted. For the first time in 11 months of living together, I said, 'Not tonight, I'm too tired.' On our wedding night! He said afterwards that he thought, 'Oh, is this what happens once you get married? The sex turns off?' (But no, it didn't.)

And so they lived happily ever after? Not quite. They lived a very interesting, eventful life, with two children, two foster-children, several pets, much travel in and out of Australia, excellent friends and many adventures, and they were happy a lot of the time.